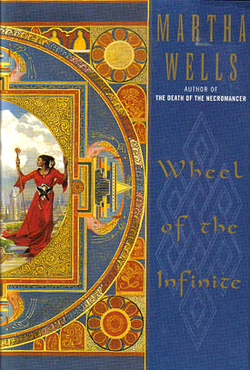

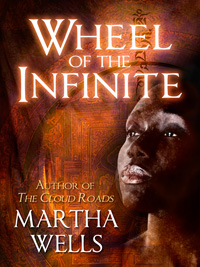

Wheel of the Infinite

Hardback: Avon Eos, July 2000.

Hardback: Avon Eos, July 2000.

Paperback: HarperCollins Eos, December 2001.

Design by Amy Halperin, cover by Donato Giancola.

A black storm is spreading across the Wheel of the Infinite. Every night the Voices of the Ancestors--the Wheel's constructors and caretakers--brush the darkness away and repair the damage with brightly colored sands and potent magic. Each morning the storm reappears, bigger and darker than before, unraveling the beautiful and orderly patterns.

With chaos in the wind, a woman with a shadowy past has returned to Duvalpore. A murderer and traitor--an exile disgraced, hated, and feared, and haunted by her own guilty conscience--Maskelle has been summoned back to help put the world right. Once she was the most enigmatic of the Voices, until cursed by her own actions. Now, in the company of Rian--a skilled and dangerously alluring swordsman--she must confront dread enemies old and new, and a cold, stalking malevolence unlike any she has ever encountered. For if Maskelle cannot unearth the cause of the Wheel's accelerating disintegration--if she cannot free herself from the ghosts of the past and focus on the catastrophe to come--the world will plunge headlong into the terrifying abyss toward which it is recklessly hurtling. And all that is, ever was, and will be will end.

eBook: (DRM-Free)

eBook: (DRM-Free)

Audiobook: narrated by Lisa Reneé Pitts. Tantor Audio, Amazon, Audible, iTunes.

|

[ Other Fantasy Novels

| City of Bones

| Wheel of the Infinite

]

| About the Author

| Bibliography

| Blog ]

|